Subscribe

On The NewsSubscribe

confirmed Your subscription to our list has been confirmed.

Paolo Roversi in Galliera musée de la mode de la ville de Paris

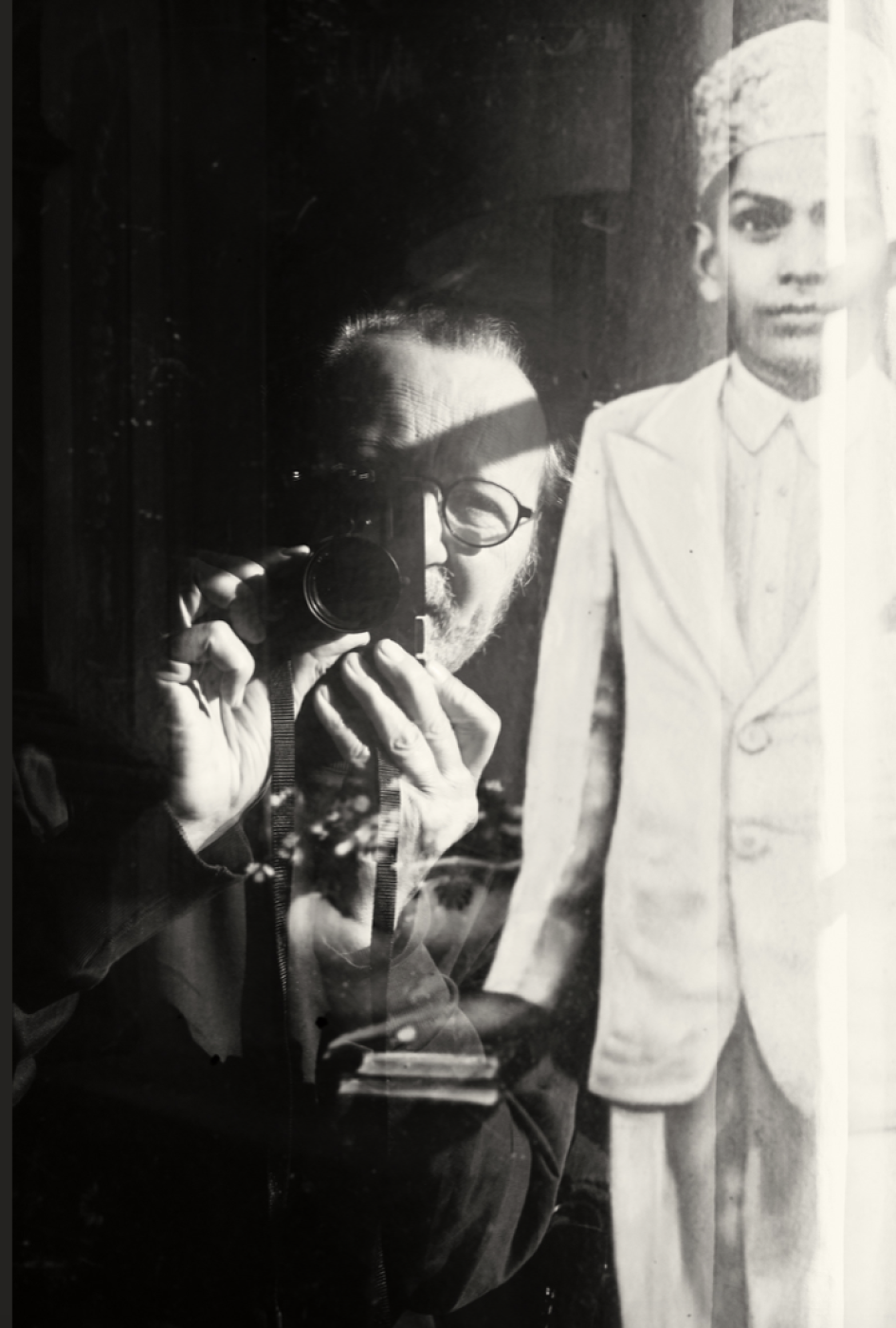

This is not just a large – the largest, actually – exhibition of Paolo Roversi’s work, it is also his first one in Paris, the city where his career as fashion photographer began in 1973. The exhibit opened in the Parisian fashion museum Palais Galliera. The organizers assembled 140 photographic works, including some that have never been seen by the public before, added things like magazines, lookbooks, invitations with Roversi’s footage, and the photographer’s Palaroids. All this was assembled by Sylvie Lécallier, the head curator of the museum’s photographic collection. Presented together for the first time as the celebration of Roversi's 50 years in photography, they show the visitors what goes into his art and how it works.

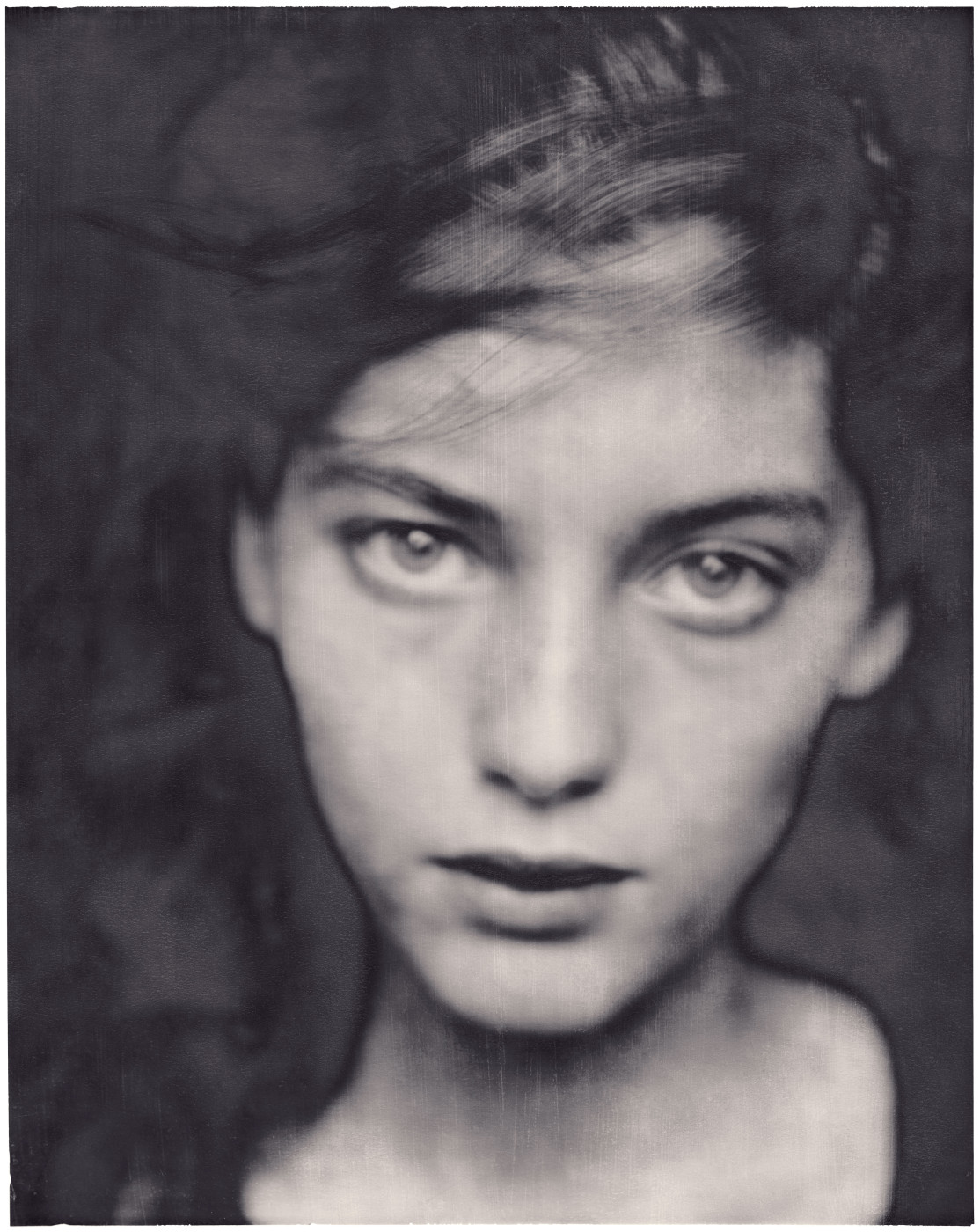

The vast majority of Roversi's works in general, and at this exhibition in particular, are portraits (although there are also photos of his favourite camera and one dog maybe also his favourite, but they, too, are portraits of sorts). And thanks to the specific nature of his work, the vast majority of the portraits’ subjects are models; he has worked with all the famous fashion models of the last 30 years, but he rarely shoots portraits of celebrities. But even when shooting the famous models, he never reproduces the clichés familiar to the public: he does not typecast his subjects as sexy goddesses, flirty girls, androgynous androids, or other popular stereotypes. In one of his interviews, Roversi says the following about his art, although he calls it “technique”, not “art”: “We all have a sort of mask of expression. You say goodbye, you smile, you are scared. I try to take all these masks away and little by little subtract until you have something pure left. A kind of abandon, a kind of absence. It looks like an absence, but in fact when there is this emptiness I think the interior beauty comes out. This is my technique."

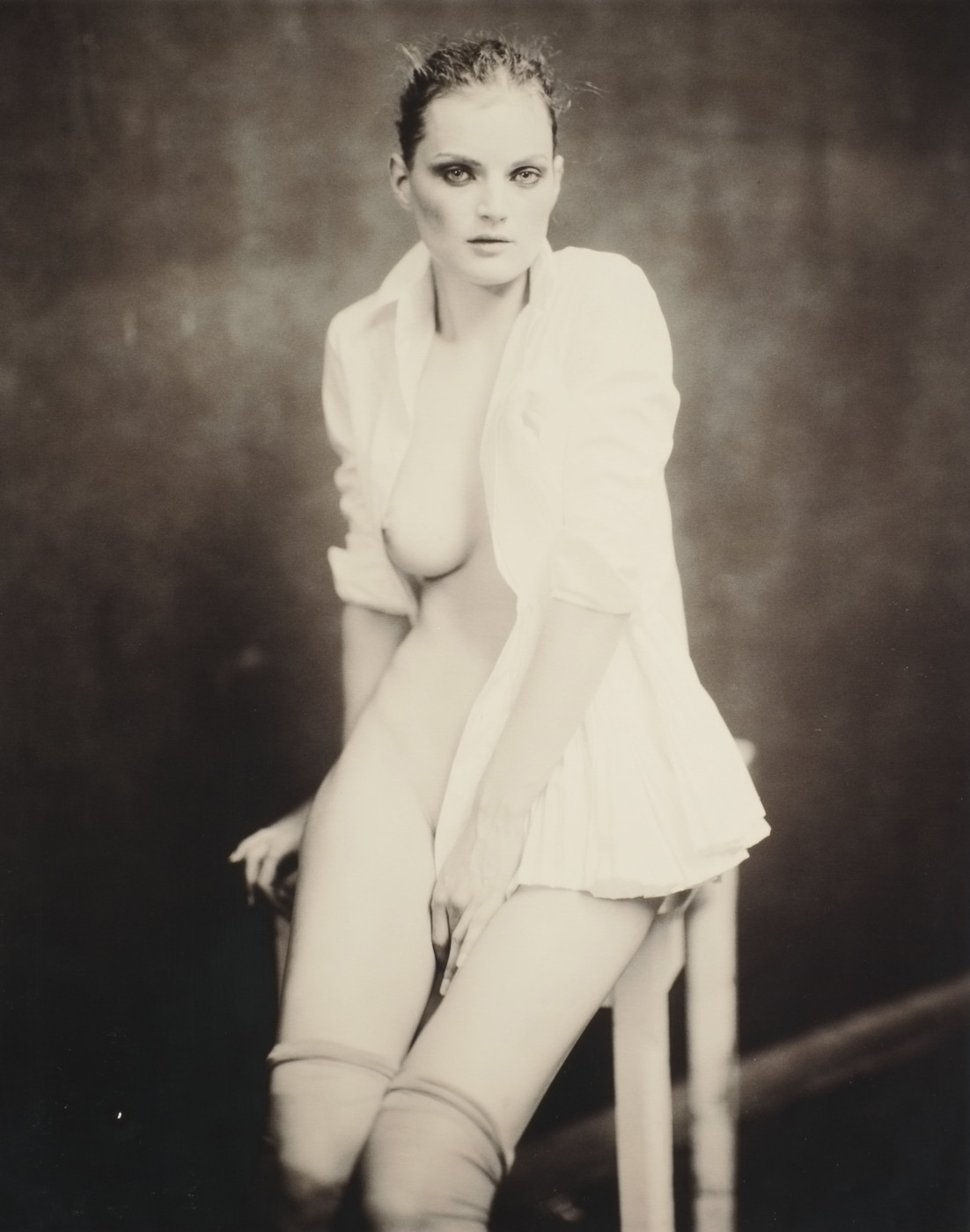

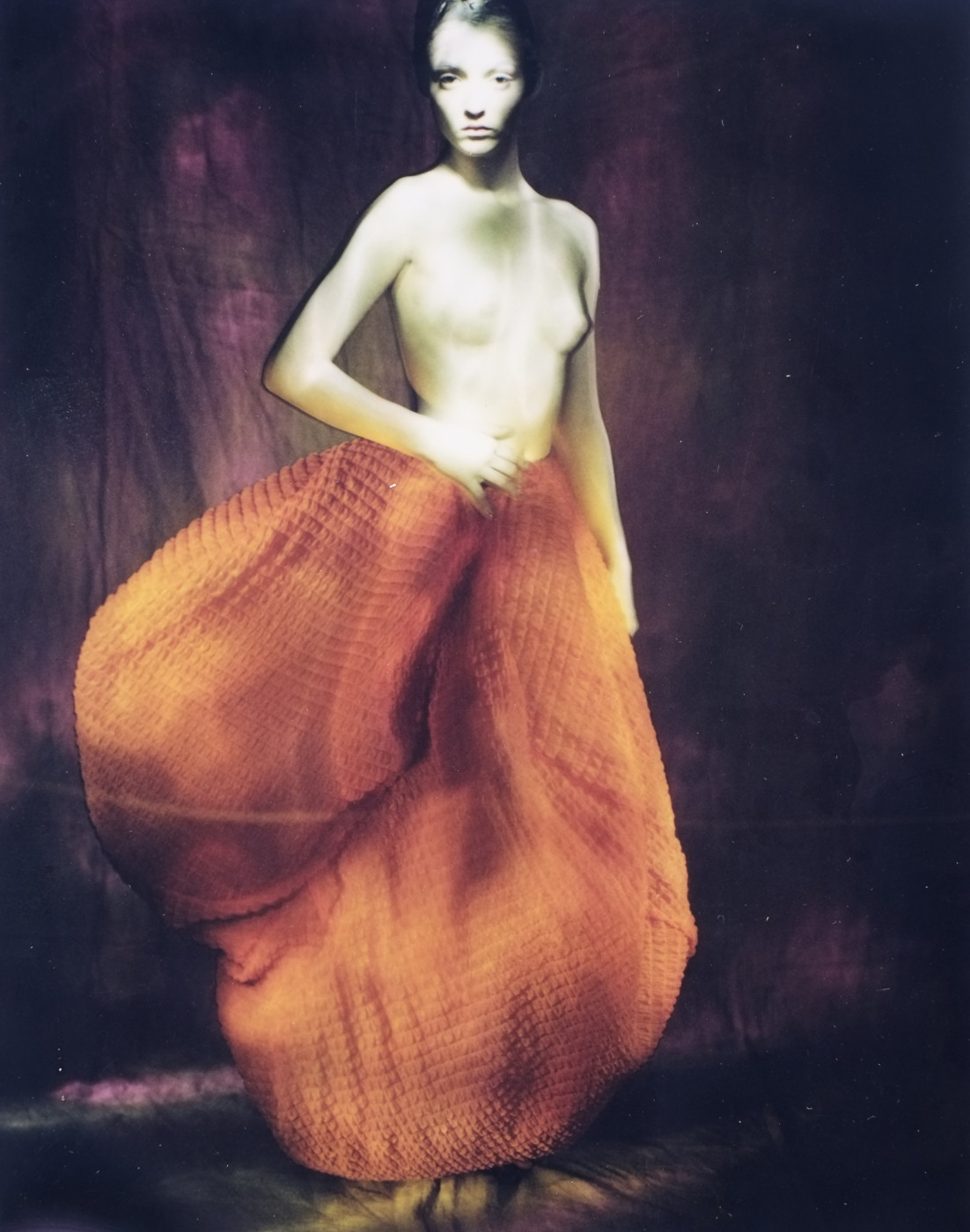

Kate Moss doesn't look like the queen of heroin chic, Natalia Vodianova doesn't look like a frightened fawn, and Stella Tennant doesn't look like Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. What happens to all of them is exactly what Roversi says: he takes away all these masks until only something pure is left. Paradoxically, this disengagement created by his camera does not amplify the distance between the viewer and the models, but reduces it, bringing them closer to us in their humanity, with all their personal idiosyncrasies. This is especially noticeable in the Nudi series, which began in 1983 with a nude portrait of Inès de La Fressange for Vogue Homme, shot at the height of her career, and then continued as his private project, where he photographed famous and not so famous models. Always in the same way – naked, full-size portraits, looking directly into the camera, under direct full light without shadows, shot in black and white, and then re-shot on a 20x30 Polaroid – and this seemingly distancing and unifying effect has created a special depth and expressiveness. They are collected at the exhibition in a separate room – and this is perhaps its most touching part, because these naked bodies are devoid of any sexualization.

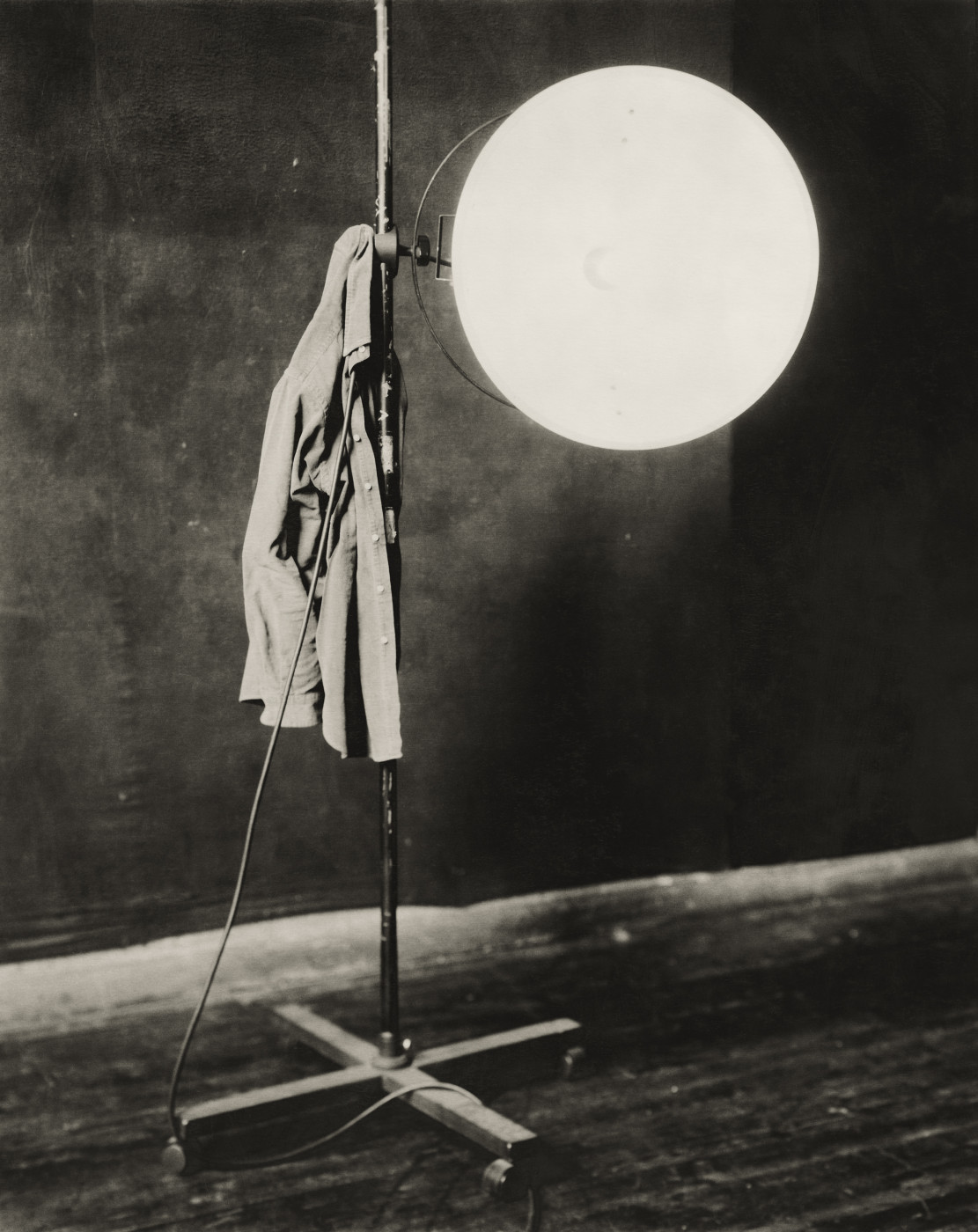

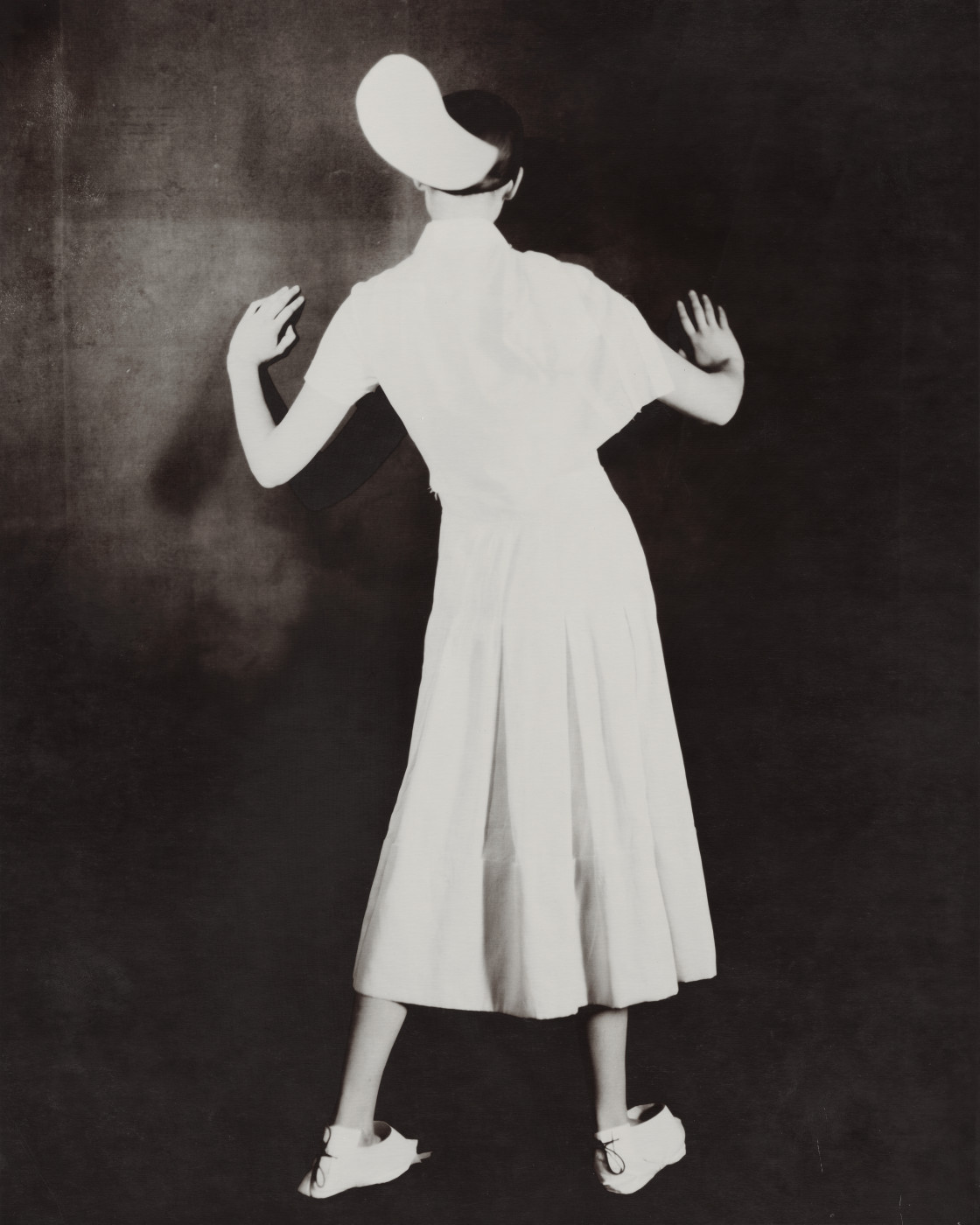

In general, Roversi likes working with the 8x10 Polaroid camera, the film for which isn’t made anymore, and the photographer as he said has bought everything he could find. This camera has come to be associated with his distinctive and very recognizable style that uses color and light to create effect of a painting. And even when he uses other cameras, the effect is there. Many have tried and are trying to copy this effect, but the result is usually something reminiscent of the work of AI. Roversi's original magical realism can be seen in detail at the exhibition – in his shoots for Vogue France, Vogue Italia, Egoïste, and Luncheon, in his campaigns for Yohji Yamamoto, Comme des Garcons, and Romeo Gigli. The work of the exhibition’s scenographer Ania Martchenko, who created several of her signature trompe-l’œil in the form of a window or a slightly open door that emit light, emphasizes the master’s use of light both metaphorically and literally.

But Paolo Roversi’s very interaction with fashion, with fashion collections, is quite unique – he shoots in a way that makes it a secondary subject of the picture, but the photographs do not cease to be fashion. As he says himself: “The clothes are a big part of a fashion picture. It’s a big part of the subject. Even if, for me, every fashion picture is like a portrait – I see and treat every image as a portrait, of a woman or a man or a boy – but the clothes are always there and they can make the interpretation of the image much more difficult.”

Courtesy: © Paolo Roversi

Text: Elena Stafyeva